It Happened Here -- Ulysses S. Grant on Horses, Smoking, Dying and Determination

The General loved horses and had been an exceptional horseman. On foot he was described as “an ordinary scrubby looking man (who) gets over the ground queerly. He does not march, nor quite walk but pitches along as if the next step would bring him on his nose” (Flood 108.) but on horseback he was magnificent. Years before, as a Cadet at a graduation exercise at West Point he and a horse named York made a record breaking jump that left the spectators breathless, and remained an Academy record for 25 years.(Flood 24. Perry13.) During the Mexican War he made a desperate ride to order up more ammunition. Racing down a two mile street exposed to enemy gunfire, he hung from the side of his mount, shielding himself from the enemy and galloping at breakneck speed the whole way. He delivered his orders unscathed as he was able to ride in and out of the Mexicans' fields of fire before the Mexican troopers had time to respond. (Flood 108-109)

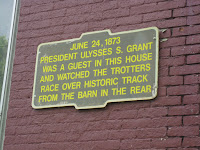

|

| near Track Entrance, Goshen |

|

| 210 Main St., Goshen |

Before they parted, however, Grant made an announcement that ominously foretold of difficult times ahead for the General. Giving his cigar case to one of of the two, Grant carefully selected a cigar and lit it. “Gentlemen, this is the last cigar I shall ever smoke. The doctors tell me I will never live to finish the work on which my whole energy is centered these days (his Memoirs) if I do not stop indulging in these fragrant weeds.” (Flood 110.)

Grant loved his cigars and had smoked from six to twenty five a day. Before he smoked cigars he chewed tobacco and smoked a pipe, which his wife Julia hated. She would regularly throw Grant's pipes away.. In 1862, Admiral Samuel Foote, commander of the gunboats attacking Fort Donnelson in Tennessee had been wounded and Grant went to him to confer on strategy. The admiral offered him a cigar which he put in his pocket. Later he lit the cigar and had started to smoke it when a staff officer rode up and told him the Confederate forces were making a vigorous attack. Grant forgot about the cigar, which went out, but he continued to carry it throughout most of the day as he went among his troops issuing orders and directing the battle. Grant's successful attack made him a national hero and his terms offered to the Confederate General, “unconditional surrender” made U.S. Grant a celebrity bringing him to the attention of Lincoln, as well. Newspaper accounts portrayed him as having smoked his way through the entire battle and for weeks to come, an adoring Northern public sent him cigars – tens of thousands of boxes of them! Grant gave away what he could, but from then on, cigars were a regular part of his life. (Flood 107-110)

It was a peach, not a cigar, that was the first harbinger of trouble for General Grant, early in June 1884. The General had complained of a sore throat but had paid it no mind until later that week Julia had set out a bowl of peaches and Grant had helped himself to one. An intensely sharp stinging sensation accompanied his first swallow of peach, and in fact he thought he had swallowed a bee. Several attempts to rinse his throat only increased his discomfort. Julia wanted him to go see a doctor but the stubborn Grant would not hear of it. His personal physician was abroad and besides, he was preoccupied with other problems. (Flood 73-75)

The

personal problems that weighed so heavily on Ulysses Grant in the

summer of 1884 were financial. As a retired United States Army

General, Grant would have been eligible for a comfortable pension,

but when he became President of the United State the law required him

to give up that pension, and there was no pension for retired

Presidents. (It would not be until the Presidency of Harry Truman

after World War II that Congress finally voted pensions for former

Presidents.)

One of Grant's sons, Buck, a budding Wall Street financier, had introduced him to Ferdinand Ward and James D. Fish. Ward and Fish offered them partnerships for $100,000 each in a new investment firm to be titled Grant and Ward. President Grant was offered a part time position for a handsome salary but was not involved in daily operations, except for signing occasional documents and lending his prestigious name to the company. At first, the firm did extremely well with the initial investors receiving a 40% dividend, when the average stock exchange return on investment was 5.5%! Most of the company's liquid assets were held in the Marine Bank, another Ward and Fish company. When New York City, the other major depositor, made a large withdrawal, a panicky Ferdinand Ward asked Grant to raise another $500,000 to keep the bank solvent. Grant did, asking help from friends and colleagues. Then Ward fled with his check. An investigation revealed the firm of Grant and Ward had solicited $16million from investors but had made only $6000 worth of stock purchases. Most of the money had gone to Ward and Fish, and to paying the early investors an exorbitant dividend to encourage other people to invest.--one of the first iterations of the "Ponzi scheme."

Not only was Grant "broke" but he felt tremendous responsibility to others he had asked to invest.

One of Grant's sons, Buck, a budding Wall Street financier, had introduced him to Ferdinand Ward and James D. Fish. Ward and Fish offered them partnerships for $100,000 each in a new investment firm to be titled Grant and Ward. President Grant was offered a part time position for a handsome salary but was not involved in daily operations, except for signing occasional documents and lending his prestigious name to the company. At first, the firm did extremely well with the initial investors receiving a 40% dividend, when the average stock exchange return on investment was 5.5%! Most of the company's liquid assets were held in the Marine Bank, another Ward and Fish company. When New York City, the other major depositor, made a large withdrawal, a panicky Ferdinand Ward asked Grant to raise another $500,000 to keep the bank solvent. Grant did, asking help from friends and colleagues. Then Ward fled with his check. An investigation revealed the firm of Grant and Ward had solicited $16million from investors but had made only $6000 worth of stock purchases. Most of the money had gone to Ward and Fish, and to paying the early investors an exorbitant dividend to encourage other people to invest.--one of the first iterations of the "Ponzi scheme."

Not only was Grant "broke" but he felt tremendous responsibility to others he had asked to invest.

The

failure of Grant and Ward would lead Grant to make a decision he had

previously avoided. For years friends and publishers had been trying

to get him to write about his wartime experiences. There was a

continuing strong interest in the Civil War. Many books had been

published and many of the war's generals and other participants had

written their stories, but Grant had not. The General didn't see himself as a writer

and was somewhat skeptical of what he could add to a story that was

already being extensively told. In January, Century Magazine,

a respected national periodical first approached the General about

contributing to a proposed series on the Civil War to be written by

some of the war's most important figures. Grant was asked to write

articles on the battles of Shiloh, Vicksburg, the Wilderness and Chattanooga.

At that time he had shown no interest, but now he was feeling burdened with a sense that he needed to do all he

could to provide for his family. Although his throat continued to

trouble him a great deal, the General threw himself into his task and

produced an article on Shiloh. The editors at

Century Magazine were delighted, but delight turned to dismay when

they read Grant's piece– essentially, a dry

analytical “after action” report that an officer might typically

submit to his superiors. With some trepidation the Century Magazine's

associate editor, Robert Underwood Johnson approached Grant to ask

him to rewrite the piece, advising him to make it “like a talk he

might make to friends after dinner, some who would know all about the

battle, and some nothing at all.” He told him the public was

especially interested in his perspective, what he “planned,

thought, saw and did.” Grant did not take offense, but instead took Johnson's criticisms to heart. Johnson said of his work

with him, “no one ever had an apter pupil” and Grant found

something he thoroughly enjoyed. (Flood 56-60)

As his condition worsened, Grant went to his physician followed by several specialists and learned he had a cancerous tumor. In

the weeks and months that followed, the pain became constant and

severe. Grant was reduced to primarily a liquid diet. He described drinking water like “drinking

molten lead.” (Flood 89.) Throat swabs of “cocaine water,”

brandy and morphine would help for a while but they

left him fuzzy headed and he could not work. (Flood 198.) Writing,

itself, was often Grant's only relief. The old soldier's abilities to

focus on the tasks at hand and wall himself off from the

fears, fatigues and discomforts he had felt on the battlefield served him

admirably in this current battle.

One

morning in mid-November Fred Grant and his father were about to sign the contract they had just received from Century Magazine for a book of Grant's wartime memoirs when they had a visitor--Samuel Clemens (aka. Mark Twain). Dramatically stopping the former President from signing, Clemens outlined a proposal Clemens offered to present to his publisher. Saying that Century Magazine grossly

under-appreciated the market for his memoirs, Clemens proposed his book should be

widely advertised and sold by subscription-enlisting veterans. With potential readers including hundreds of thousands of veterans contacted to buy the book and

making an initial payments for the book, before printing began, Clemens believed the book could be huge, but not entail the risks a large publication run might pose; becoming much more successful than a book

simply printed and deposited on bookstore shelves. After several days of hesitation the Grants agreed and the next day, Clemens presented Grant with a $50,000 advance check.(Flood 99-103. Perry 82-90, 115-117.)

Through the first half of 1885 Grant continued to battle his cancer, and write with organizational help from one of his sons and stenographic help from a former wartime aid, Adam Badeau. Sometimes the pain would be so bad for days that he could not write, but then he would rally and soldier on.

News of his illness had leaked out and his apartment in New York City was besieged by newspaper reporters, curiosity seekers, well wishers and people of all sorts offering him home remedies. By early June it was getting hot in the city and Grant and his doctors decided he needed a cooler, quieter place away from the crowds. The owner of the new Balmoral hotel, outside of Saratoga offered him the use of a "cottage" on the extensive grounds of the hotel. The "cottage" was actually a big two story house with a large room suitable for an office/bedroom on the first floor and a spacious wrap-around porch on three sides. His family purchased for him a "bath chair"--a large wheeled chair that looked like a cross between a modern wheelchair and a rickshaw, first developed for spa treatments in Bath, England.

|

| Rte 9, Wilton |

News of his illness had leaked out and his apartment in New York City was besieged by newspaper reporters, curiosity seekers, well wishers and people of all sorts offering him home remedies. By early June it was getting hot in the city and Grant and his doctors decided he needed a cooler, quieter place away from the crowds. The owner of the new Balmoral hotel, outside of Saratoga offered him the use of a "cottage" on the extensive grounds of the hotel. The "cottage" was actually a big two story house with a large room suitable for an office/bedroom on the first floor and a spacious wrap-around porch on three sides. His family purchased for him a "bath chair"--a large wheeled chair that looked like a cross between a modern wheelchair and a rickshaw, first developed for spa treatments in Bath, England.

The plan was that he could be wheeled around the porches to take in the cooling, pines scented breezes from whichever direction they happened to blow. A short distance away was an overlook where the family hoped to take the General for an occasional change of scenery.

The plan was that he could be wheeled around the porches to take in the cooling, pines scented breezes from whichever direction they happened to blow. A short distance away was an overlook where the family hoped to take the General for an occasional change of scenery. |

| Mt. McGregor Rd., Wilton, off U.S. 9 |

On

the afternoon of July 19th Grant put down his pencil and

handed his writing tablet to his stenographer, who for the last month

had mainly assisted him by reading back to him the drafts, that Grant

himself had written out. He was finished. His memoirs, which he

completed in just under a year, would fill two volumes, 1,215 pages,

– 291,000 words. They would be critically acclaimed, and frequently

compared, favorably, to Caesar's Commentaries. Julia would

receive a check for

$

200,000 and eventually paid a total of $450,000, in royalties.

The

following day, Grant suggested to his doctor they take the bath chair

to the eastern overlook. Grant returned pale and

exhausted. The next four days his condition worsened, as his family

were summoned and gathered around him. The General began to drift in

and out of consciousness. On the morning of July 23d, he died. His

son Fred impulsively stopped the clock on the mantle of the room

Grant occupied, slept in and wrote in throughout much of the

summer. The room at “Grant Cottage” has been kept as it was that

Thursday morning. The mantle clock reads 8:08.

Flood, Charles Bracelen. Grant's Final Victory: Ulysses S. Grant's heroic last year. 2011

Perry, Mark. Grant and Twain: the story of a friendship that changed America. 2004

Flood, Charles Bracelen. Grant's Final Victory: Ulysses S. Grant's heroic last year. 2011

Perry, Mark. Grant and Twain: the story of a friendship that changed America. 2004

Marker of the Week--

Q.--Who is buried in William Few Jr.' s tomb?

A.--Not William Few Jr.!

If this marker strikes you as a little odd, it does me too. William Few, Jr. was a legitimate founding father of Georgia who organized militia resistance to the British, served in the Congress under the Articles of Confederation and was a delegate to the Constitutional convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Few was elected one of the first U.S. senators from Georgia, then served as a federal judge of the Georgia circuit. In 1799 he retired and moved to Manhattan where he believed he could better further his business interests. Few became president of City Bank of New York and an assemblyman in the New York Assembly, then, City Alderman followed by other positions. He retired to Fishkill-on-Hudson (Beacon) in1815; dying and buried there in 1828.

In

1973, in the run-up to the American Revolution Bicentennial, Georgia asked for

their founding father back. New York and the Protestant Reformed Church of Beacon

complied.

| ||||

| Protestant Reformed Church, Rte 9D, Beacon |

No comments:

Post a Comment