It Happened Here--In Precarious Positions

From a distance it might seem like a

drama played out in the deep South in the days following

Reconstruction. A black man waits in fear with manacled wrists, as a mob

gathers demanding he be turned over to them. The officer and his

deputies try to force their way through the mob with the man to the judge's office.

The black man is battered and bruised as he is pulled

first one way, than another as the mob tries to pull him from the

officers. They succeed, wresting him away and throwing him in a small

skiff to carry him from Troy to West Troy, (now Watervliet.) But the

telegraph is faster than the boat, and when they arrive the police

are waiting there to re-arrest the man. As a large part of the mob

pours across the river in a ferry boat and various commandeered watercraft, the police

and their prisoner are holed up in a judge's office on Broadway.

Again the scene is repeated with the mob storming the building, this

time ignoring shots fired into the crowd by unnerved officers. They

retake the black man, now dazed and bleeding and he is thrown into

the back of a wagon and spirited away to Schenectady. Spirited

away—to what? A tree, a rope, and a lynching?

No—to

Freedom!

Charles Nalle was born into slavery in

Culpepper Virginia about 1821. His mother, Lucy, was a light skinned

mulatto girl and his father was, officially, unknown, but generally

known to be Peter Hansbrough, a wealthy planter whose plantation was

near the plantation where Charles' mother was enslaved. The year

Charles was born Hansbrough bought Lucy and her children when his

neighbor, her owner, died. Charles was brought up as house slave and

coachman, assigned to drive his master's carriage and care for his

horses. Hansborough gave Charles to his son, Blucher Hansborough,

and Charles continued as his half-brother's coachman. Charles

married Catherine “Kitty” Simms who lived on the nearby Thom's

planation. Slaves were often encouraged to marry, but forced to live

apart in nearby plantations. This gave plantation owners an important

lever over their slaves, as it gave masters the power to permit or

restrict the contact slaves had with their spouses and families,

dependent on their good behavior.

Though Nalle was treated better than

many slaves – certainly much better than field hands in the deep

south, the insecurity and inhumanity of his everyday life weighed

heavily on him. Though Blucher Hansborough promised never to sell

him, one day following a major setback of a fire that destroyed a

barn containing most of the plantation's wheat harvest Charles and a

friend were set upon by local whites, at the behest of Blucher.

Beaten and chained together with two field hands they were

transported to Richmond's slave market to be sold. Only a lack of

interest on the part of bidders saved Nalle and his companion from

being sold away. (A glut of slaves in the marketplace and tight money

prevented Nalle and his friend from the fate of the two field hands

who were auctioned off, never to see their homes and families again.)

Neither Charles nor his friend commanded the minimum asking price

Hansborough required, and they were returned home.

A few years later another crisis loomed

when Kitty's master died and his property was divided among his heirs.

Perhaps because she was a young women with four young female children

to care for she may have been considered more of a liability than an

asset in the harsh economic calculation of slavery, so she was freed

by her master. For the young black woman, this news was little

better than if she had been bound away. Virginia law prohibited

free-blacks from living in Virginia, as did most of the other "slave" states, so she was forced to move out of state. But if she went

to a “free” state, Charles would certainly never be allowed to

visit. So, she chose “Washington City” (D.C.), seventy five miles

away, where freed slaves were allowed, but strict “black codes”

gave slaveholders confidence they could control their slaves, and

might encourage Hansborough to permit Charles an occasional visit.

In August 1858 Charles and a friend

were given one week travel passes to go to Washington under the

supervision of some of Hansborough's relatives and with prior

notification of the Washington police. In Washington they managed to slip away from their escorts, make their

escape and link up with the Underground Railroad, an association of

people who aided fugitive slaves. From there they made their way to

Philadelphia, probably in the hold of a small coastal schooner, then

on to Albany and the Underground Railway Station run by a freeborn

black man, Stephen Meyers. In Albany Meyers offered the fugitives

a choice . They could either take a ticket to continue on by train to

Canada or stay on in upstate New York, in a rural area and be set up

with jobs, there. Charles chose the latter option, believing it would

be easier for his family to make their way up to Albany, and that by

working, he would be able to send them money to make it happen

sooner. A deciding factor may have been the presence of Minot Crosby,

a teacher who had befriended him in the South, and probably helped

facilitate his escape. Crosby had abruptly left his teaching position

and fled from Virginia when Crosby's abolitionist leanings and

Underground Railroad activities had become known. The teacher had

settled in Sand Lake, Rensselaer County and was teaching at the

Female Seminary, located there. At the time, rural Rensselaer County

was enjoying a boom in lumber production, so work was readily found

for Nalle, an experienced coachman, driving lumber wagons.

While there was much abolitionist

support in New York State, (the Albany and Troy UGRR stations openly

solicited monies from donors, even holding public fund raising

events), New York was deeply divided. Most Democrats were

pro-slavery, and supported the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 which

required “free” states and federal commissioners to assist

Southern slaveholders recover their runaway slaves. Living near

Charles was a young, struggling lawyer, Horatio Averill. Averill had

practiced law for four years but had lost his position in a New York

law firm following an accusation of embezzlement. He had recently

worked for a small local newspaper, but had been let go from that

job, as well.

One of Charles' ambitions was to learn

to read and write – skills denied him when he was a slave. Crosby

was tutoring him, and helping him write letters. Somehow,

Averill or one of his siblings overheard one of their conversations

or surmised from the contents of one or more of his letters that

Nalle was a runaway slave and that Blucher Hansborough was his former

master. Averill wrote Hansborough advising him of Charles'

whereabouts, and offering to represent Blucher as his counsel to

facilitate the slave's recapture and legal extradition to Virginia.

Charles suddenly left Sand Lake for

Troy in the early spring of 1860. Whether he suspected something or

was seeking the society of a larger black community is unclear. He

found lodging in the house of William Henry, a local grocer and employment as a

coachman for Uri Gilbert, a wealthy industrialist whose factory built

railway coaches on nearby Green Island.

On April 27, 1860 Nalle was running an errand for Gilbert's wife using Gilbert's carriage to pick up bread at a local bakery. He had just climbed back onto the carriage when he was grabbed from behind by two men. One wore the star of a U.S. Deputy Marshall. Charles stared in horror when he recognized the other as Jack Wale, a rough man he knew from his former Virginia home, who sometimes worked as a fugitive slave catcher for the local planters. Wale fastened a heavy set of manacles on him triumphantly announcing these were the same handcuffs he had used on Charles youngest brother when he transported him to the Richmond slave market, to be sold several months before. The pair pulled Charles onto the pavement and dragged him several blocks to the Mutual Bank Building where the U.S. Commissioners had a second floor office. There, affidavits and other paperwork were completed for his transportation back to Virginia. Wale, of course, was there to testify to Charles identity, as was Averill who testified to Charles' time in New York, and what he had learned about the fugitive.

Meanwhile, one of Gilbert's sons had gone looking for Nalle, when he had not returned. After finding the abandoned carriage, he contacted the grocer with whom Charles was staying. After an inquiry at the local jail turned up nothing, he heard from eyewitnesses that Nalle was being held at the U.S. Commissioners office, and Henry began telling his contacts in the Underground Railroad and the local Vigilance Committee, an organization to aid blacks, that had formed in cities in the North after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act.

On April 27, 1860 Nalle was running an errand for Gilbert's wife using Gilbert's carriage to pick up bread at a local bakery. He had just climbed back onto the carriage when he was grabbed from behind by two men. One wore the star of a U.S. Deputy Marshall. Charles stared in horror when he recognized the other as Jack Wale, a rough man he knew from his former Virginia home, who sometimes worked as a fugitive slave catcher for the local planters. Wale fastened a heavy set of manacles on him triumphantly announcing these were the same handcuffs he had used on Charles youngest brother when he transported him to the Richmond slave market, to be sold several months before. The pair pulled Charles onto the pavement and dragged him several blocks to the Mutual Bank Building where the U.S. Commissioners had a second floor office. There, affidavits and other paperwork were completed for his transportation back to Virginia. Wale, of course, was there to testify to Charles identity, as was Averill who testified to Charles' time in New York, and what he had learned about the fugitive.

|

| The Mutual Bank Building, today |

| ||

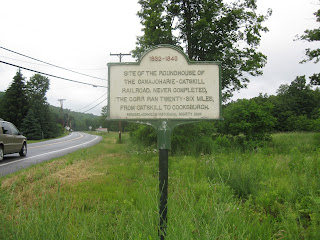

| Plaque Commemorating the Nalle Rescue in Troy |

Even with reinforcements from the local police, the Commissioner and Deputies were faced with the daunting task of bringing Nalle several blocks to the judge's office through this huge emotion-charged crowd. As the police cleared the stairway bringing their manacled prisoner out into the daylight, something they least expected happened. The decrepit old black women lunged forward latching onto their prisoner with a powerful grasp, attempting to wrench him from the officers, and revealing herself as Harriet Tubman1 the famous abolitionist who had personally led scores of blacks to freedom. Tubman's actions signalled the outbreak of pandemonium and set in motion the events outlined in the beginning paragraph.

|

| Broadway, Watervliet |

After about a month of hiding, Charles was freed when the people of Troy and West Troy arranged to buy his freedom. Hansborough accepted $650, having few other options open to him. Charles returned to Troy, and returned to work as Uri Gilbert's coachman. After four years he was finally reunited with his wife and family. The federal government decided to prosecute those they could identify as having taken leading parts in the riot. Subpoenas were issued but then events got in the way, as the United States became embroiled in a much, much bigger conflict, and they were forgotten.

1Tubman was in town visiting her cousins on her way to a speaking engagement in Boston. She had perfected this disguise/persona in several of her rescues in the deep South.

Next Week-- In Precarious Positions Part II and

the Marker of the Week returns.

.